My KPFA - A Historical Footnote

The Griller String Quartet

e quattribus unum

In 1960, when I was still working in the UC Berkeley Music Library, Sidney Griller asked me to record a rehearsal of Jerome Rosen’s clarinet quintet, performed by the composer and the Griller String Quartet, who were in residence in the university’s music department. (Rosen had just become the first chairman of the newly formed music department at UC Davis.) It came out so well that I was later allowed to give it an airing on KPFA; you can listen to it HERE. Hearing the Grillers play again, and in one of my own recordings, takes me back to a whole chapter of my musical education and of four fine musicians, with very distinct separate identities, of whom I was both collectively and indivually fond.

Back in college when I was discovering the chamber music repertoire, there were two string quintets that reached out and grabbe

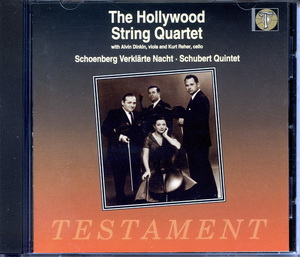

Back in college when I was discovering the chamber music repertoire, there were two string quintets that reached out and grabbe d me by the scruff of the neck: the Schubert C major, D.959, and the Mozart G minor, K.516. Both of them I first heard on LP in performances by ensembles whose recordings survive to this day, still at the pinnacle of interpretative perfection. The Schubert recording was made by the Hollywood String Quartet plus Kurt Reher in 1950 and blessedly survives on a Testament CD, SBT 1031 (see footnote below). Its adagio would mark a transformation in my later life, but that’s another story.

d me by the scruff of the neck: the Schubert C major, D.959, and the Mozart G minor, K.516. Both of them I first heard on LP in performances by ensembles whose recordings survive to this day, still at the pinnacle of interpretative perfection. The Schubert recording was made by the Hollywood String Quartet plus Kurt Reher in 1950 and blessedly survives on a Testament CD, SBT 1031 (see footnote below). Its adagio would mark a transformation in my later life, but that’s another story.

The recording of the Mozart with which I first became familiar was by the Griller Quartet plus Max Gilbert for Decca way back in 1948. Originally released on three 78s, it came out subsequently on an LP, LXT 2515. I still have my original copy, heavy and stiff as a shellac 78.

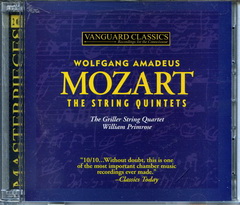

Fortunately the Grillers recorded it again in 1959, along with the other five, when the technology was infinitely better. Vanguard Records were able to use the university’s wonderful new recital venue, Hertz Hall [right]. I was working in the Music Library next door and so I was able to slip across for most of the recording sessions. Available on two Vangaurd CDs, ATM-CD-1204, it was history in the making: Classics Today wrote, “Without a doubt, this is one of the most important chamber music recordings ever made.”

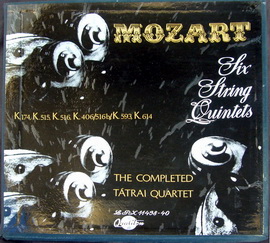

An extravagant claim, which I’m not inclined to argue with. But years later I would discover the performances of these quintets by the “Completed” Tatrai Quartet on the Hungarian Qualiton label, LPX 11438-40. (So far as I’ve been able to determine, it was never released, at least as a set, on CD.) They give the Grillers a run for their money, particularly in the later K.593 quintet. What they most importantly demonstrate is that the concept of the “definitive performance” is utter rubbish. How could four human beings who had lived through the second world war in central Europe, and came together immediately after it had ended, play this classically restrained but heart-rending music in the same way as an English quartet whose lives had been, by comparison, relatively tranquil? And who would want to live without either set of performances?

An extravagant claim, which I’m not inclined to argue with. But years later I would discover the performances of these quintets by the “Completed” Tatrai Quartet on the Hungarian Qualiton label, LPX 11438-40. (So far as I’ve been able to determine, it was never released, at least as a set, on CD.) They give the Grillers a run for their money, particularly in the later K.593 quintet. What they most importantly demonstrate is that the concept of the “definitive performance” is utter rubbish. How could four human beings who had lived through the second world war in central Europe, and came together immediately after it had ended, play this classically restrained but heart-rending music in the same way as an English quartet whose lives had been, by comparison, relatively tranquil? And who would want to live without either set of performances?

But back to the Grillers. I was close enough to them to observe how a quartet of musicians could work together for over thirty years without becoming enmeshed in each others lives. (The attempt to do so often leads to both personal and musical disaster.)

Sidney Griller [right] was a family man, married in 1931 at the age of twenty to Honor Linton, with whom he lived his entire life and raised a couple of children. In later years, back in London and teaching at the Royal Academy where he had begun his training, he and Honor would maintain their lifelong reputation for hospitality.

Second violinist Jack O’Brien and violist Philip Burton were “confirmed bachelors” (the phrase used in those circumlocutory days). I first knew them in 1953 when as a student at Cal I occupied a bed-sitter tucked under a massive redwood house [left] on Shasta Road in the Berkeley hills. It was one of three such houses built on an enormous, mostly wild hillside plot by a retired British engineer named Andrew Shirra

Second violinist Jack O’Brien and violist Philip Burton were “confirmed bachelors” (the phrase used in those circumlocutory days). I first knew them in 1953 when as a student at Cal I occupied a bed-sitter tucked under a massive redwood house [left] on Shasta Road in the Berkeley hills. It was one of three such houses built on an enormous, mostly wild hillside plot by a retired British engineer named Andrew Shirra  Gibb. He and his wife occupied one, I was under the second which was unoccupied, and Jack and Philip had the third [right]. Gibb's guiding principles are set forth in Charles Keeler’s The Simple Home. Polymath Gibb later wrote a huge book which attempted to explain Jungian psychology to the general reader.

Gibb. He and his wife occupied one, I was under the second which was unoccupied, and Jack and Philip had the third [right]. Gibb's guiding principles are set forth in Charles Keeler’s The Simple Home. Polymath Gibb later wrote a huge book which attempted to explain Jungian psychology to the general reader.

Of the four quartet members, Philip was the scholar. His enormous library of Shakespeariana lined the walls of their living room. He was also a James Joyce enthusiast and told me of having encountered a Dublin taxi driver who had read all of Finnegan’s Wake. “It’s easy if you’re from these parts,” he had said. “It’s the way we talk.”

When Andrew died, he left the property to Jack and Philip. The hillside plot had become a wildlife sanctuary, and it was their collective wish that, valuable as it would have been if split into building sites, it should be preserved intact. When I visited Jack in the 90s, Philip had died and he was living alone. The grounds were much as I remembered them, though a little wilder, and Philip’s library still lined the walls of the living room. Jack seemed touchingly grateful to talk to someone who had known them together some forty years before.

The fourth member of the quartet was the cellist Colin Hampto n. A somewhat mournful creature, he lived alone. One of his students was a rather plain girl named Bonnie Bell. A Paolo and Francesca romance gradually developed between them -- their eyes met, they kissed, and they read no more that day – but with a happy ending. Colin’s face became wreathed in smiles and Bonnie, who soon became Bonnie Hampton, blossomed into a truly beautiful woman with a distinguished career in her own right as performer and teacher.

n. A somewhat mournful creature, he lived alone. One of his students was a rather plain girl named Bonnie Bell. A Paolo and Francesca romance gradually developed between them -- their eyes met, they kissed, and they read no more that day – but with a happy ending. Colin’s face became wreathed in smiles and Bonnie, who soon became Bonnie Hampton, blossomed into a truly beautiful woman with a distinguished career in her own right as performer and teacher.

Such liaisons across the years can indeed produce miraculous results. Valerie Eliot, when I knew her fifteen years ago, still radiated the magnetic intensity which had given such joy to her beloved Tom and which she devoted to organizing his life and later his literary estate.

The quartet disbanded in 1961 after Philip's death and in 1964 Sidney was invited by his alma mater, the Royal Academy, to come back to London and teach chamber music performance. I followed two years later as Pacifica Radio’s London Correspondent, but I never got in touch with him until 1993, when I noted in the Guardian birthdays list that he was exactly twenty years and four days older than me. On a whim I phoned to offer my congratulations. He remembered me immediately and urged me to phone again and set a date to come around for tea. It’s one of my regrets (I have so many!) that I never got around to doing so. In November he died at eighty-two (only three years older than me!), the last surviving member of his great eponymous quartet. This vignette is a small attempt to help prevent their memory, as people as well as musicians, from dying along with them.

For further details of their early career, see Nicholas P. Lafkas: Quartet In Residence November 1950

©2010 John Whiting

May 2010: Working on Alan Rich's obit, I found the following in his list of "works created by people I respect, which have made my process of getting from day to day a lot more rewarding than it might otherwise have been."

Schubert: Quintet in C: There is no way to explain the surge of creative energy that overtook the frail frame of Franz Schubert in the year of his death; we just accept, and marvel. On a Sunday in 1951 I climbed Mt. Tamalpais with friends in the afternoon, and heard the Hollywood Quartet with Kurt Reher — studio musicians who had formed a “serious” ensemble of extraordinary sensitivity — play the Schubert Quintet at night, and the memory of that day will always remain. (There are other excellent performances, but none like this, none that sustain the lyric line of the slow movement as these people did.)

But time moves on. There is now an incredible recording by the Belcea Quartet, whose Wigmore Hall performance was broadcast recently on the BBC. I hadn’t heard of them, but apparently they’re quite famous. Trained (and joined in this performance) by the cellist from the old Alban Berg quartet, their lineage is impeccable. At first listening, their extremity of dynamics and rubato is almost shocking, but it soon becomes apparent that their grasp of structure and content is profound. And they’re so young – but then, so was an equally remarkable violinist I knew thirty years ago. The incredible richness of sound reflects the extra cello in the lower register more dramatically than any performance I’ve ever heard.